First in Flight (Almost)

One hundred years ago next week, Samuel Langley conducted a manned flight experiment that could have made Stafford County's Widewater as well known today as Kitty Hawk, N.C.

Date published: 10/4/2003

The genius of Samuel P. Langley and the impact of aviation during the past 100 years was celebrated in grand fashion yesterday in this Stafford County community along the shore of the Potomac River.

"We invite the world to join us in honoring Langley's grand achievement on its 100th birthday," said President Bush. "There is no better site to celebrate American ingenuity and persistence than here at Widewater where the course of history was changed forever."

Speaking from the steps of the First in Flight Visitor Center to a crowd of 35,000 that filled the Langley National Memorial Park, Bush said that since 1903, the names Langley and Widewater have inspired scientists and inventors throughout the world"

AH, WHAT MIGHT have been.

If Samuel Langley's test flight at Widewater in the fall of 1903 had been a success, the Wright brothers would be a footnote in aviation history, Kitty Hawk, N.C., would offer little more than sand dunes with an ocean view, and Virginians would be driving cars with "First in Flight" license plates.

And, of course, Widewater would be a national shrine and a world-class tourist attraction--especially next week during what would have been the centennial celebration of Langley's grand success.

"I guess Widewater becoming famous just wasn't in the cards," said Tom Crouch, the senior curator at the National Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

"But for anyone reading a newspaper during the time before Langley's trial, it seemed fairly likely that Widewater would be the site of the first manned flight."

There were several reasons the public expected the 69-year-old Langley to win the race for successfully putting the first piloted plane into the air and landing it safely.

First, he was arguably America's foremost scientist at the time. Langley was a self-taught scholar with a background in mathematics, architecture and astronomy. He was a pioneer in astrophysics. And he was the secretary of the Smithsonian.

Second, his project was well-financed. In addition to $23,000 from the Smithsonian, Langley had convinced the federal government in 1898 to contribute $50,000, in part because the military hoped he would deliver an aircraft that could aid America's cause in the war against Spain.

And third, the so-called Aerodrome that Langley was about to launch from the top of a houseboat off the shore at Widewater was of almost identical design to the unmanned model planes he had successfully flown seven years earlier.

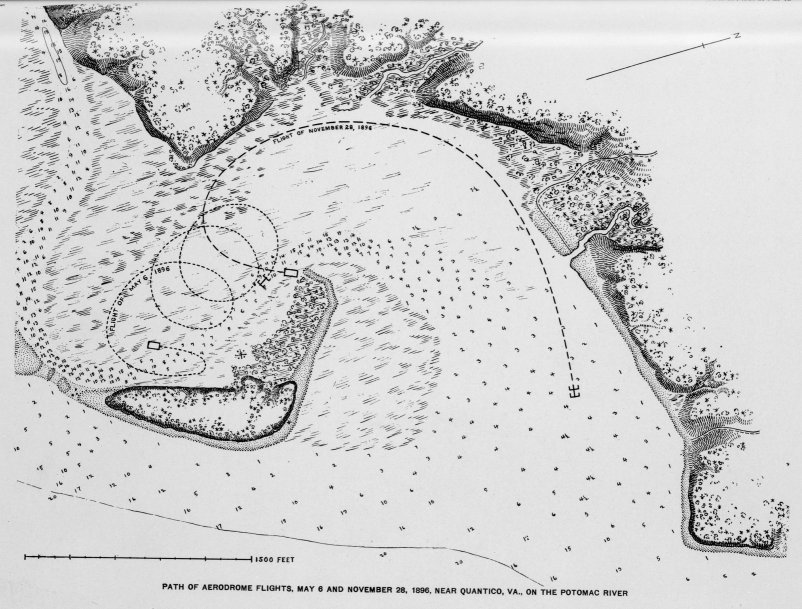

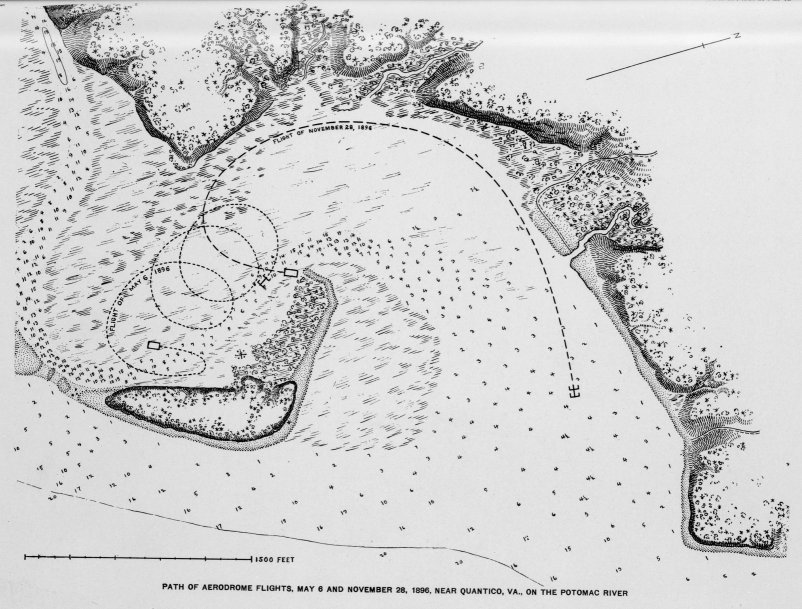

One of those 1896 test planes--launched near Chopawamsic Island in the Potomac near the present-day Quantico Marine Corps Base--covered a distance of about three-quarters of a mile and achieved a speed of more than 25 mph. Langley's model planes for those experiments had a wingspan of about 14 feet and were powered by a small steam engine.

The 1896 tests were witnessed by Langley's friend and colleague, Alexander Graham Bell.

The flying machine "resembled an enormous bird, swooping steadily upward in a spiral path until it reached a height of about 100 feet in the air," wrote Bell.

When the steam gave out and the propellers stopped, the aircraft "settled as slowly and gracefully as it is possible for any bird to do." Bell concluded that "no one who was present on this interesting occasion could have failed to recognize that the practicability of mechanical flight had been demonstrated."

The 1896 tests allowed Langley to lay claim to the first successful flight of an unpiloted, engine-driven, heavier-than-air craft of substantial size.

"Those early tests really represented the peak of Langley's aeronautical career," Crouch said. "They were very significant in the history of aviation."

So, what went wrong seven years later when Langley and his assistant, Charles M. Manly, tried to launch a piloted aircraft at Widewater?

"The problem was the machine itself and Langley's approach," said Crouch. "He did just about everything wrong that the Wright brothers did right.

"The Wright brothers decided the engine was not the key. They could calculate just how much power they needed, and they didn't care whether or not the engine was anything to write home about. They put their time and energy into the airplane--the structure, the guidance system and propeller research."

Crouch said the Wrights had a clearer vision.

"They wound up with an engine that wasn't great, but they knew it would work," he said. "Langley built the world's most advanced aeronautical engine. But he mounted it on an airplane incapable of flight."

Indeed, the water-cooled radial engine designed by Manly and inventor Stephen M. Balzer generated 52 horsepower--a remarkable achievement for the time.

But the wings of Langley's "Aerodrome A" were composed of four wood-frame panels, covered with linen and arranged in tandem pairs on either side of a tubular metal framework. One writer described it as "a gigantic, well-meaning dragonfly."

For propulsion, two pusher propellers were mounted between the wings. They were driven by shafts and gears connected to the centrally mounted engine.

The aircraft had a wingspan of nearly 50 feet and was more than 52 feet long. It was 11 feet tall and weighed about 750 pounds--including the pilot, who was to be Manly.

The whole thing looked "exceedingly complicated," according to a description in The Fredericksburg Daily Star less than two months before the test flight. "Amidships is a great mass of wheels, rods, boilers, pistons and various mechanical devices."

Langley thought the best way to launch his aircraft was with a spring-loaded catapult off the top of a houseboat.

"The catapult is practically a gun and the flying machine a huge missile," stated The Daily Star.

But immediately after its launching at Widewater at about 12:15 p.m. on Oct. 7, 1903, the aircraft plunged into the Potomac at a 45-degree angle. One newspaper reporter who witnessed the test flight said the plane entered the water "like a handful of mortar."

A report the next day in The New York World described the experiment as "a complete failure" and stated "at no time was there any semblance of flight."

The article described the scene in detail: "Professor Manly started the motor, which worked well The big machine moved easily along the 70-foot track in the launching apparatus and took the air fairly well. A five-mile breeze was blowing and for a moment the machine stood up well, but its failure was immediately apparent.

"It turned gradually downward. The declination was so positive that Professor Manly saw at a glance that but few movements of the second-hand on the stopwatch he wore on his left knee would be recorded before both he and the scientific ship would be floundering in the waters of the Potomac.

"It was a moment of anxiety for the safety of the navigator, but fears were instantly relieved as his head emerged above the surface. He had sustained no injury. His face reflected his disappointment at the result."

"One thing that is rather startling is that the lowest point on the Langley craft was the cockpit and the pilot," said Crouch. "Even if they had a successful flight over water and a safe landing, the pilot would be under the water when it was all over.

"My sense is that they were in a hurry. [Langley's] line of thinking might have been just to shoot this thing across the water for a few hundred yards to satisfy his critics and then get back to work on solving his problems."

Because of his government funding and his considerable ego, Langley was an easy target for criticism. His aircraft became known as "The Buzzard" in many press reports. One article in The Fredericksburg Daily Star, published two months before the manned test flight, dismissed the entire project as "a fiasco and a farce."

The newspaper stated that the tests conducted by Langley's team of scientists had only "succeeded so far in demonstrating to the world something not exactly new and very much in keeping with the well-established fact that whatever goes up is bound to come down."

After expressing frustration about the veil of mystery surrounding the project, the article concluded: "we affirm once more that Professor Langley should furnish some excitement or resign his job."

Despite all the media attention, however, Langley really wasn't as close to success as the public thought, according to Jim Cross, the lead interpreter at Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, N.C.

"Although he was a superb scientist, Langley was unable to overcome the engineering difficulties," Cross said. "Langley's primary problem was that he tried to build and fly a powered machine before he had any true idea of flight control. He tried to achieve powered flight by brute force of an engine and propellers."

By contrast, Cross said, the Wrights' craft was structurally and aerodynamically sound and had a system of flight control.

"Their system of control is still in use today in everything that flies," he said.

According to the Smithsonian's Crouch, the Wrights knew what was needed was a single machine with systems--the aeronautics, propulsion and control--that had to mesh.

"They knew that was the only way to get off the ground and get back safely," Crouch said. "The Wrights were intuitive engineering geniuses. They decided early on that control was the core issue. And they never lost sight of that, while Langley gave it almost no thought."

Langley was delayed in Washington and was not present at the Widewater test flight. Afterward, both he and Manly expressed confidence in the project and blamed the setback on the launching mechanism.

However, Langley should have known better than to simply scale up his models to create the full-size aircraft and he should have given more thought to the strength of his materials and construction methods, according to author Walter J. Boyne in "The Smithsonian Book of Flight."

"Langley did not appreciate perhaps the most obvious need of all: the pilot should know how to fly," wrote Boyne. "Manly had no opportunity to familiarize himself with the Aerodrome even to the limited extent of taxiing before being flung off the houseboat like a giant clay pigeon."

Cross said the Wright brothers were aware of Langley's efforts, had corresponded with him and even invited him to Kitty Hawk to observe some of their experiments (a trip that Langley's schedule did not permit).

"There was no real competition between them," he said. "They were each working toward a common goal. But the Wrights were confident that they were on the right track and suspected that Langley was missing some major points. They were interested in his work, but were not overly concerned that he was going to be successful."

After reading about Langley's failed test at Widewater, Wilbur Wright wrote a colleague, "I see that Langley has had his flight, and failed. It seems to be our turn to throw now, and I wonder what our luck will be."

While the Wright brothers did not benefit from Langley's technology, they did benefit from his work in other ways.

"Through his research, Langley concluded that heavier-than-air flight was possible with the engines of the day," Cross said.

"Coming from such a well-respected member of the scientific community, it helped elevate the belief in manned flight from the 'crackpot' level to a matter worthy of serious scientific study and consideration."

Said Crouch: "I think the Wrights might have been inspired by Langley's interest early on. Just the fact that a scientist of his reputation was interested in flight was energizing for the Wrights. But I don't think they ever had a lot of confidence in what he was trying to do."

Two months after the Widewater experiment, Langley's flight team tried again--this time closer to Washington near where the Anacostia River empties into the Potomac.

"The results were equally disastrous," wrote curator Peter Jakab in an article on the National Air and Space Museum Web site. "Just after takeoff, the Aerodrome A reared up, collapsed upon itself, and smashed into the water, momentarily trapping Manly underneath the wreckage in the freezing Potomac before he was rescued, unhurt.

"Langley again blamed the launching device. While the catapult likely contributed some small part to the failure, there is no denying that the Aerodrome A was an overly complex, structurally weak, aerodynamically unsound aircraft."

As the anticipated climax to his 17 years of aviation research, Langley's second failed test was severely criticized in the press. One report stated that the only thing Langley could make fly away was government money.

"We hope that Prof. Langley will not put his substantial greatness as a scientist to further peril by continuing to waste his time, and the money involved, in further airship experiments," stated an editorial in The New York Times.

"The disappointment was extraordinary," said Crouch. "There was the public embarrassment and congressional hearings. He died less than three years later. That wasn't just because of his failure to fly. But that was a major disappointment in his life."

It was in death, however, that Langley cast a shadow over the Wright brothers' success.

In 1914, aviation pioneer Glenn Curtis modified and improved the Langley Aerodrome A and conducted several successful straight-line flights. The aircraft then was displayed in the Smithsonian and identified as the world's first airplane "capable of sustained free flight."

Orville Wright, stung by the Smithsonian's unwillingness to give him and his late brother credit for inventing the airplane, loaned the brothers' 1903 aircraft to the Science Museum in London in 1928 in protest.

It was 1942 before Smithsonian officials finally clarified the history of the Aerodrome A, and 1948 before the so-called Wright Flyer was returned to the United States and donated to the museum.

Langley's Aerodrome A will be on display again beginning on Dec. 15 when the Smithsonian opens its new Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles Airport. And Langley's legacy has included an aircraft carrier, a NASA research center and a large Air Force base in Hampton--all named in his honor.

Manly, too, deserves credit for designing the world's first radial engine designed for flight, the same basic type of engine that took Lindbergh to Paris and powered America to supremacy in the air during World War II.

Mary Cary Kendall, who has spent most of her life in Widewater, has a family connection to the October 1903 test flight, which took place in the Potomac just off her family's property.

"My grandmother said that Langley's assistant, Mr. Manly, stayed at our home [Richland] during the time they were preparing for the flight," Kendall said.

"And my mother, who was a child at the time, said she was out on a rowboat with other local residents to watch the day it happened. Some of them even got tiny pieces of the wreckage to keep as souvenirs."

Crouch said Langley chose the stretch of the Potomac along Stafford County for his flights--both in 1896 and again in 1903--for several reasons.

"He wanted to get a little bit away from Washington and all the attention from reporters," Crouch said. "And, at least in 1896, he chose Chopawamsic Island because of the hunting club there and the fact that they wouldn't have to live on the houseboat.

"Another factor was that the river is wider there. Since he was taking off and landing on the water, he wanted as much room as possible."

Kendall hesitated when asked if it would have been good for Widewater in the long run if Langley's 1903 test flight had succeeded.

"It's so hard to speculate," she said. "I know at the time it was a huge disappointment for Professor Langley and the Smithsonian. And it was a big event in Widewater. I guess members of my family talked about the 'flying machine' long after it was forgotten by most people.

"But there's nothing here I'd really want changed. I love the peace and serenity, and the tranquil view. And if they had succeeded, Widewater--and especially Richland--would be entirely different.

"I think of this area as a little bit of heaven. So maybe things worked out for the best after all."

LEE WOOLF, a longtime reporter and editor with The Free Lance-Star, is bureau manager at the newspaper's North Stafford office. Call him at 540/720-5470, or e-mail him at lwoolf@freelancestar.com

Date published: 10/4/2003

===============================

Related Links:

http://www.nasm.si.edu/research/aero/aircraft/langleyA.htm

http://home.att.net/~dannysoar2/Langley.htm

http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Prehistory/Last_Decade/PH5.htm